Articles

Determine the age of antique radios

When you get an old radio, the first thing you want to know is its value. To determine the estimated cost of the kit, you need to find out the manufacturer and age of this set.Usually you look at the make and model number on the back cover (sometimes on the front panel) and then on the Internet or in specialized catalogs for collectors, find all the information you need. For example, see Filco radios Identification Guide.

But if you bought an incomplete radio at a fleamarket or found it in the attic, it may not have inscriptions on the front panel or back cover. On the other hand your radio, perhaps, never had obvious identifiers to begin with. How to identify a rare device in that case?

There are a number of methods to help determine the age and manufacturer of a radio to within about five years. Of course, this will not replace the opinion of a specialist, but will allow you to come up with a reasonable estimate of the age of your set.

The basics will give you a good idea of what's going on.

- Does it look ancient? It probably is.

- Does it look Art Deco? It's probably 1930s.

- Does it have FM? Then it'll be after 1954.

Common sense is a great tool.

Appearance

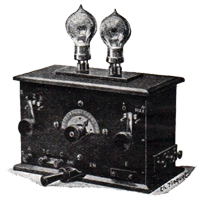

The best guide to a radio's age is the way it looks:| Before the 1920’s, the cabinets for radio apparatus were often made from Ebonite and/or wood and tended to look rather like early scientific equipment, with the valves sticking out of the top or the front of the set. In the early-1920’s, "breadboard" construction was common, as exemplified by the range of Atwater Kent radios of this period. |  |

| By the mid-1920’s, "coffin" style wooden cabinets were becoming the standard for table-top sets, usually with separate loudspeaker – often a horn type. Slant fronts were often used to jazz these coffins up a bit, especially between 1924 and 1926. Some manufacturers, eg. Philco and Atwater Kent manufactured cases from steel at this time.

By the late-1920’s, "low-boy" and "high-boy" style floor-mounted sets had appeared, sometim with doors to disguise the set as a regular piece of "parlour" furniture. |

|

| After 1927 radios were still mainly wood, but the valves tended to be inside the box, out of harm's way. It was not until about 1932 that most radios started to look as we expect an old radio to look, with a tuning dial calibrated in wavelengths and a built-in speaker behind a piece of decorative cloth. |  |

| If the set looks very Art Deco, it's probably in the 1932 to 1936 range, because after this they tended to look like radios, rather than avantgarde talking furniture. It is about this age range when the Bakelite cabinets started to take off. Art Deco styling can be found on both wood and Bakelite cabinets. In these years, the earlier the radio, the more likely it is to have a small, quite simple dial, with no station names marked on it. |  |

| If the set has Short Wave on it and a big glass dial with lots of technicolor markings, it's a good bet that it's 1936 or later. There was a fashion for "All Wave" sets at this time, although many which had a Short Wave range did not pick up a great deal of stations on Short Wave. Any set which was even vaguely up with the latest fashion had to have as many colors of print on the dial as possible, and also as many station names as the manufacturers could squash on. Most of these stations would never be receivable on that set in the UK, but that didn't put them off. |  |

| By 1938 the level of complexity built into even quite average radios had increased and most sets had some sort of "feature" to sell them. Most featured large speakers and quite powerful outputs, and almost all had very colorful backlight dials. Quite a good proportion had some kind of preset tuning, usually using press-buttons, though some had contraptions almost like telephone dials where the station was dialled up. The most adventurous had motor tuning, where the push-button activated a motor, which tuned the set. |  |

| The war made a big difference to radio design, with the press-button tuning and other complexities vanishing almost overnight. The 1940 sets were much more austere, and most had very few, if any, flashy features. At the end of the war, companies had to return to the domestic set market in a bit of a hurry, and many put out models very closely related to the products they were producing in 1940 when production of domestic sets ceased. To sort out the pre-war from the post-war here can be hard. |  |

| The late 1950s brought a craze for piano-key wavechange switches, and for a while, everybody had to have them. This lasted in some companies until the mid sixties, but in general the craze died down by about 1960. |  |

In 1954, domestic FM broadcasting became a reality and the first of the FM sets were released. Obviously the cheaper sets did not have FM coverage even many years after this date, so a set with FM will be after 1954 and probably somewhere near the top of that company's range.

After this you are in the transition period between valves and transistors, and you get some funny things happening. About 1965 you get radios which look like valve sets, but contain a transistor chassis and usually a very large battery.

These soon died out, though, as TV at last pushed the radio out of the living room and made it wander around the house as a portable.

What does it say on the dial?

The tuning dials usually have station names printed on them, and by checking the name and the position on the dial, you can gain a good idea of when the radio was designed.- The Long Wave National transmitter changed from Daventry (4XX) to Droitwich in 1934. So if it says Droitwich on the dial, it's after 1934.

- The regional network closed down for the war, so the late 1939 and early 1940s offerings tend to be labelled with "BBC" or something equally non-committal in a lot of places on the dial.

- The inscriptions "Police" or "Aircraft" on the tuning scale suggest that the receiver was made before the Second World War.

- The Forces program present on the dial tells you that it's a wartime set.

- The Home service was named by 1946, so a radio with Home on the dial will be post war. The Light and the Third followed later. The regional scheme was re-introduced very soon after the war, and most of the post-war sets have some indication of a regional network on the dial. So even if it doesn't call it the Home service, it might call it Northern, Midland, etc.

- The 1940s and 1950s sets don't reveal much by their dial markings, because there was a period of stability in the allocation of various frequencies allocated to various countries due to the implementation of the Copenhagen Agreement, where all this was decided, just after the war. Lots of dials at this time have the magic word "Copenhagen" in the corner, often out of sight until the dial is removed from the radio. That refers to the frequency plan, not where the dial was made or who by.

The Valves

Most of what turns up these days tends to be post-war. The 1940s things look very much like the 1950s things, so the best way to sort one from the other is on the basis of the valves inside. The valves can tell you a lot about the age of the set. |

The very early valve sets use R valves, which are bright-emitters. These light up like light-bulbs when in use, and nice early examples will have spherical glass bottles and maybe a little glass pip on the top where the seal was made when the valve was manufactured. Later offerings tend to be more pear-shape and lack the top pip. However, they will still be pretty ancient, and may well have a number (such as R5V) on them somewhere. These will date the set roughly as 1927 or before. |

|

After the bright emitters came the dull emitters. These were built quite like the later versions of the R valve, but the filament had a more efficient coating on it, and hence could be run at a lower temperature, so these only glow dull red when in use. These were used in some sets as replacements for R valves, so if your set has little inspection grilles for each valve inside and a rheostat for each filament, it's quite possible that it originally had R valves. Sets using only simple dull-emitter triodes will most likely date from 1930 or before. After this date, more efficient valves became available. |

|

The next development was the pentode valve. This came in two forms. There was the HF type for the radio end of the set, and then there was the audio type for loudspeaker-driving duty. The HF pentodes made possible much greater gain at high frequencies, and hence allowed more stations to be received with fewer valves, and less adjustments and tuning controls to contend with. The audio pentodes also allowed greater gain, but at this end of the set, the greater gain meant that the chances of a station being strong enough to drive the loudspeaker were improved. |

|

After this, the valve makers put some effort into making valves for mains-powered sets, which by 1932 were becoming a reality. The major difference is the addition of a cathode, so that the heater only heats the cathode, and the cathode emits the electrons and works the rest of the valve. This meant that AC could be used to heat the valves without causing hum problems. The mains valves were used until the war with fairly minor developments. One of the major changes was the need for more pins on the valve base, and for the first time, valves with seven pins were made. The numbering systems were reasonably logical, though every manufacturer had their own. |

|

An interesting development was the 1933 Catkin valve, by Osram. These had the same characteristics as some of the ordinary mains types, but due to advances in methods for joining metal to glass, these could be made without a conventional bottle. This meant that the anode formed the outer surface of the valve proper, and in order to provide built-in screening, the diamond-punched metal can was put around the outside. These must have been expensive to make because they did not stay in production long and are comparatively scarce now. |

|

About 1936, the continental valve makers were making more complex valves, and putting them on their new side-contact base. This was never a popular range of valves in British sets, but Mullard did market the range in the UK, due to its links with Philips in Holland. Most UK radio manufacturers ignored the new valves and carried on just as they had been. |

|

About 1937, the American Octal base made its entry into the UK domestic set market. This base had eight pins, which allowed more complex valves, and even two simple electrode structures in the same valve. HMV, Marconi and GEC were among the first to use the Octal valves. They developed their own variations on the standard American valves. With the Octal valve, the standard heater voltage changed from the previously normal 4V to 6.3V |

|

Not to be left out, other British valve makers introduced Octals as well. Mazda introduced their own variation on the theme in 1938, with a similar base which did not fit in the American Octal socket, and had the old fashioned 4V heaters. These Mazda octals did catch on with the companies which used Mazda valves, such as Murphy, and they made some fine sets with them, before and after the war. The Mazda octal valves are very reliable and even today have a good reputation. |

|

Mullard launched their Octal range in 1939. They used the American Octal base, but used the electrode structures from the Euro-trash side-contact range which had been a poor seller before. The resulting range of valves were accepted almost universally by radio manufacturers, and became very popular in some of the last pre-war radios, and many of the 1940s sets made after the war. |

|

During the war, a lot of work was done on developing valves to give higher gain at higher frequencies. Probably the most notable was the EF50, which was a basic tool of the early Radar installations, and it is cerain that this valve helped to shape the war. They were used after the war in some televisions released about 1946, but most were made for the military and used in military applications. In the 1950s, the government sold off huge numbers of unused surplus stock EF50s, and almost every radio enthusiast making his own gear used one for something. |

|

After the war, there was a move towards smaller radios. This forced smaller valves. One of the first moves in this direction was the American "Bantam" valve, otherwise known as "GT" shape, which was a standard American Octal valve, with a narrow, straight-sided, reduced-height bottle, which took up less room. These were in use in America well before the war, because Midget radios were part of the American scene from the mid thirties onwards. |

| However, wartime advances in the manufacture of valves made possible new types of valve using new techniques. It was no longer necessary to have a valve which consisted of a bottle stuck onto a base where the pins lived. It was now possible to make a flat-bottomed bottle, and set the pins directly into the glass. This made the base redundant and a lot of space could be saved. | |

|

One of the first of the smaller bases was the B7G, which seems to have been imported from America, and was pioneered in this country by Brimar and Marconi and Osram. These little valves were dramatically smaller than anything which had gone before and made possible some very compact sets. However, their reliability has proved to be only moderate, probably due to the higher temperatures reached by the smaller, more compact structures inside. |

|

A later addition was the B8A base, which was introduced in 1947 with a metal band around the bottom. This base was backed heavily by Mullard, and Mazda again made their own version, this having a metal pressing with the band around the bottom and a locating spiggot in the middle, between the pins. However, unlike the situation with Octals, most sockets would accept either variant. These valves were used in sets from about 1949, but were still being fitted into new designs as late as 1953 or 1954. After this date, they were still widely used, but usually only for some of the valves, with newer valves on different bases used for the other jobs. In 1953 the base was revised and made entirely of glass. Most examples are all-glass. |

|

In 1951, the Noval base was introduced. This had nine pins, and was pretty well the last of the valve bases introduced. Valves on this base started to be used as early as 1951, but it is not until about 1954 that sets using only Noval valves turn up. By 1956 the Noval was used almost universally, but it is possible to date a "late 1950s Noval set" a little closer by looking at the types used. If the set has FM, the give-away sign is in the FM head unit. A pair of pentodes (EF80) will put the set in the early FM era, say 1954/55. A double triode (ECC85) will put it after this. |

* The IF amplifier valve will give some clues too. The early Novals used EF85, but after about 1957, the EF89 replaces it and gives more gain. A set using EBF89 as an IF amplifier is usually after 1959.

** Strange output valves such as ECL86, ELL80 and ECLL80 point to a radio made in the 1960s, usually in Europe. Most of these sets also use a metal rectifier in place of a rectifier valve, and have at least some Germanium diodes as detectors, usually for FM, normally using an EBF89 as IF amplifier and AM detector.

Very popular "magic eye" was introduced in 1935 – more of a sales gimmick than a useful gadget, though some manufacturers retained some form of meter, eg. Philco, with the "Shadow Meter". The "Magic Eye" is a specialized vacuum tube commonly used in older radios as a visual indicator of received signal strength to help the user tune into a radio station.

Component Dates

Manufacturing dates can be found on some components inside the radio: electrolytic capacitors are the most common, especially from the 1940s. The reason electrolytic capacitors are dated is because they deteriorate with age, especially early types, and especially if not used. A date older than a few years may indicate to the service technician that the capacitor should be replaced as a precaution against failure.

The idea in this case is that the radio should be made later than the date observed on one of its components. In the case of the electrolyte, it was probably installed in the radio within a few months of its date of manufacture. However, care should be taken as some components, especially electrolytes, may have been replaced at some point during the life of the radio. For example, an electrolyte dated 1947 is found in a 1939 radio. Replaced components are usually (but not always) obvious.

The dates can also be seen on the speaker cabinets, as well as the QA/QC stamps on the chassis and cabinets.

Patents

The serial number plate, tube layout sticker or other documentation with the set often contain one or more patent numbers notices. The set must have been manufactured after the most recent patent (but possibly several years after, so this is not a very precise measure). These are almost pretty useless for identification.

Other parts

"Dog-bone" resistors were introduced in the 1920's and started to drop out of use by the late-1940's. At this time, cylindrical resistors with color code bands became the norm, but some old stock "dog bones" were still being used through the 1950's.

"Dog-bone" resistors were introduced in the 1920's and started to drop out of use by the late-1940's. At this time, cylindrical resistors with color code bands became the norm, but some old stock "dog bones" were still being used through the 1950's.

Capacitors can also provide a clue to age: wax-coated paper capacitors were the norm for by-pass and audio coupling capacitors from the late-1920's through mid-1950's, however, plastic encapsulated paper capacitors were introduced in WWII as a way of providing enhanced moisture-proofing. By the late-1950's these plastic-encapsulated paper capacitors were in widespread use, soon to be replaced by the much more reliable plastic film (eg. Mylar) types. Tubular and disc ceramic capacitors were developed during WWII and these were present in some sets by the mid-1940's onwards.

Capacitors can also provide a clue to age: wax-coated paper capacitors were the norm for by-pass and audio coupling capacitors from the late-1920's through mid-1950's, however, plastic encapsulated paper capacitors were introduced in WWII as a way of providing enhanced moisture-proofing. By the late-1950's these plastic-encapsulated paper capacitors were in widespread use, soon to be replaced by the much more reliable plastic film (eg. Mylar) types. Tubular and disc ceramic capacitors were developed during WWII and these were present in some sets by the mid-1940's onwards.

Electrolytic capacitors evolved from the large can "wet" electrolyte types of the early 1930's through "dry" (electrolyte paste) types in both can and axial form by WWII and afterwards.

Electrolytic capacitors evolved from the large can "wet" electrolyte types of the early 1930's through "dry" (electrolyte paste) types in both can and axial form by WWII and afterwards.Silver mica capacitors were often encapsulated in rectangular Bakelite cases in the 1920's through 1940's.

Pre-WW2, magnet technology was such that strong, focused-field permanent magnets that would retain their magnetism for many years could not be produced economically. Therefore "electrodynamic" loudspeakers were the norm, the field coil on the electromagnet often serving a dual or even triple purpose (also as a smoothing choke and bias resistor). The output transformer was usually mounted on the speaker frame. This type of loudspeaker can be identified by three to five wires running from the chassis to the loudspeaker. During WWII, "Alnico" alloy magnets were produced that allowed long-lasting permanent speaker magnets to be produced and post-WWII their use became the norm.

"Bias cells" - small dry cells that provided bias for amplifier circuits - they look like modern day "button" cells - were introduced by some manufacturers, eg. Rogers-Majestic, in the mid-1930's and their use died-out during WWII. Read more: Mallory Bias Cells.

References:

1. Gerry O'Hara (2011) Dating Your Radio – A Beginner's Guide

2. Rusbridge, R.G. Dating Your Radio

Add comment:

| Name: | ||

| code protection:* | ||

| email:* | ||

Main

Main